In Autumn 2015, Sea-Watch began a maritime rescue operation with speedboats off the coast of Lesbos, Greece. In just five months, we were able to save around 4,000 people from drowning. After the EU-Turkey deal in March 2016, the numbers of refugees declined sharply, so we reduced our engagement to observing the situation and put our rescue boats into standby. The dangerous refugee route from Turkey to Greece is still in use until today despite the deal, whose implementation necessitates critical supervision in the public sphere, particularly given that media coverage has largely dissipated. People are still regularly drowning in their attempt to reach Greece.

Video: The only two survivors of a shipwreck in April 2017 tell their story

Our mission

We want to fix the eyes of the media back onto the Greece-Turkey route. With the EU-Turkey deal, things have become neither better nor safer for refugees and migrants. The camps and hotspots are the object of constant criticism due to their catastrophic supply situation and inhuman living conditions, but do not receive the necessary attention or the action from the EU which this miserable humanitarian situation in the Aegean requires.

In July 2017, Sea-Watch returned to the Aegean with its original flagship in order to restart the ‘Aegean Observation Mission’ along the coasts of the Greek islands and report on the acute humanitarian situation at the invisible walls of Europe. The Sea-Watch 1 has room for a crew of up to 8 people and is fully equipped with up-to-date maritime communications technology. Our ship serves as a base for the crew and a platform for documentation and observation.

Through our network of activists and intensive exchange with aid organisations, shocking news reached us time and again in the past few months, particularly from the refugee camps on Lesbos (Moria and Kara Tepe) and Chios (Vial and Souda). The overfilled camps are becoming more and more like prisons, in which people have to live for up to 16 months under inhuman conditions with a catastrophic lack of supplies, or are arbitrarily locked up. The number of people with psychological illnesses is enormous, and suicide, along with hunger strikes, is often the only way of dealing with the sheer despair

“We came to Europe to find shelter, but Europe rejects and imprisons us. Refugees are not criminals.” (Arash Hampay, refugee from Iran).

“We came to Europe to find shelter, but Europe rejects and imprisons us. Refugees are not criminals.” (Arash Hampay, refugee from Iran).

In July 2017 these conditions in Camp Moria led to further peaceful protests, which were violently repressed by the police with the use of tear gas. “If I had known what was awaiting me and my family in Greece, we would rather have died in Syria,” reported a Syrian father recently.

On the islands, police and military forces are in operation, and their number has increased in recent months in order to further reinforce ‘Fortress Europe’. Refugees and migrants are not brought to the camps with spare capacity on the Greek mainland until their asylum application has been processed on the islands. This situation makes their day-to-day suffering much worse, as the stream of incoming boats has not stopped in spite of the deal.

At sea, we see a similar picture. Migrants and refugees tell of attempts to capsize their boats in order to intimidate people on the dangerous path across the sea. Meanwhile, the coast of the European Union has been militarised like never before. NATO warships and Frontex units patrol alongside the Greek and Turkish coastguard, with eyewitnesses continually reporting ‘push-backs’.

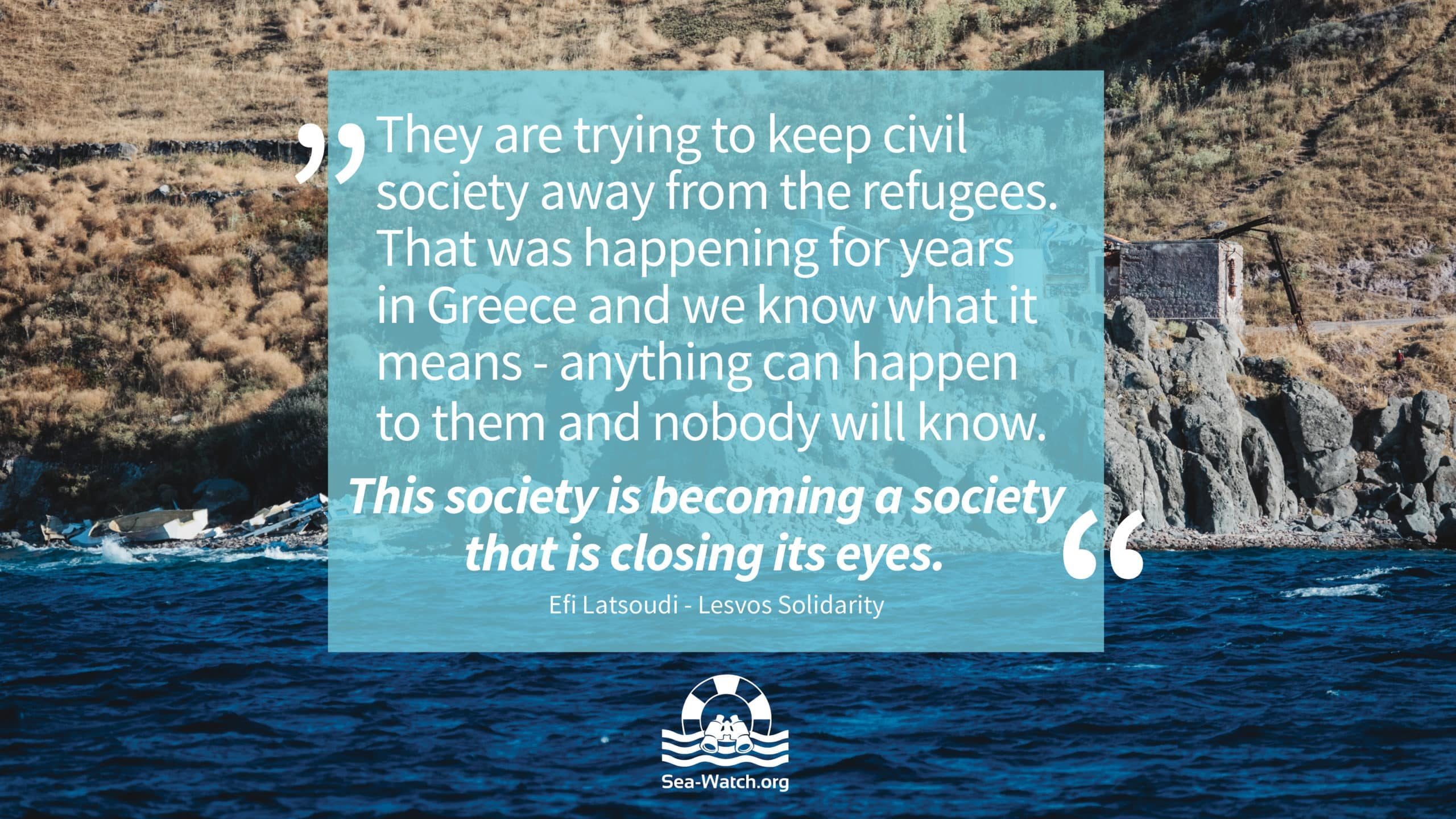

In recent times the work of aid organisations on and around the water has been tightly regulated and even prevented by Greek authorities and coastguards, despite the fact that their support in maritime rescue is imperative. These organisations are not allowed to work on their own or rescue boats in distress without asking for permission from the coastguard. The number of attacks from the right-wing scene (such as Golden Dawn) on refugee camps and voluntary helpers from aid organisations has also increased.

A pattern can be recognised which leads us to understand that there is a genuine interest in removing all witnesses who follow these events at sea from the scene. The humanitarian situation on land and sea continues to deteriorate, and for this reason Sea-Watch is back in the Aegean in order to shed light on the severe effects of the 2016 deal between Turkey and the EU, document its impact on human rights and publicise this. With the help of our partners on the scene, our goal is to improve the situation for refugees and migrants on land and at sea.

Maritime rescue in the Aegean is primarily arranged by Frontex and the Greek coastguard. Their successful work interests us just as much as the cases which fail to meet humanitarian standards. Only an active, present civil society can ensure that human rights are upheld and abuses uncovered.

Maritime rescue in the Aegean is primarily arranged by Frontex and the Greek coastguard. Their successful work interests us just as much as the cases which fail to meet humanitarian standards. Only an active, present civil society can ensure that human rights are upheld and abuses uncovered.

Furthermore, we would like to enter into dialogue with governmental rescuers on an equal footing in order to encourage improvements in rescue procedures and find possibilities to improve the largely inhuman conditions in the refugee camps on the islands.

The ‘Aegean Monitoring Mission’ aims, as well as keeping an eye on the actions of the entities involved and the invisible walls of the EU, to support the projects and initiatives of the volunteers, locals and aid organisations who engage tirelessly for humanity.