Merchant Vessel Involvement in Sea Rescue Operations

Overview of relevant cases spotted by Airborne Operations in 2020

Due to the seizure of NGO vessels and the lack of a state-led European Search-and-Rescue (SAR) programme, operations which retrieve people from distress at sea currently rely primarily on the shipping industry. Captains and crews of merchant vessels are frequently left alone by European authorities to deal with unattended distress cases for which they often lack adequate equipment and supplies. Delays of goods and cancellations of contracts due to a lack of coordination by responsible authorities may also occur, leading to financial losses for shipping companies. For these reasons, a trend has even developed in avoiding the main migration routes of the Central Mediterranean.

For almost 3 years, the crews of the aircraft Moonbird and Seabird* have witnessed the lack of support given to merchant vessels involved in SAR operations, and also the non-assistance of several vessels, as a result of European policy. This factsheet outlines a summary of selected cases involving merchant vessels which were witnessed in 2020.

Overview of relevant cases spotted by Airborne Operations in 2020

Due to the seizure of NGO vessels and the lack of a state-led European Search-and-Rescue (SAR) programme, operations which retrieve people from distress at sea currently rely primarily on the shipping industry. Captains and crews of merchant vessels are frequently left alone by European authorities to deal with unattended distress cases for which they often lack adequate equipment and supplies. Delays of goods and cancellations of contracts due to a lack of coordination by responsible authorities may also occur, leading to financial losses for shipping companies. For these reasons, a trend has even developed in avoiding the main migration routes of the Central Mediterranean.

For almost 3 years, the crews of the aircraft Moonbird and Seabird have witnessed the lack of support given to merchant vessels involved in SAR operations, and also the non-assistance of several vessels, as a result of European policy. This factsheet outlines a summary of selected cases involving merchant vessels which were witnessed in 2020.

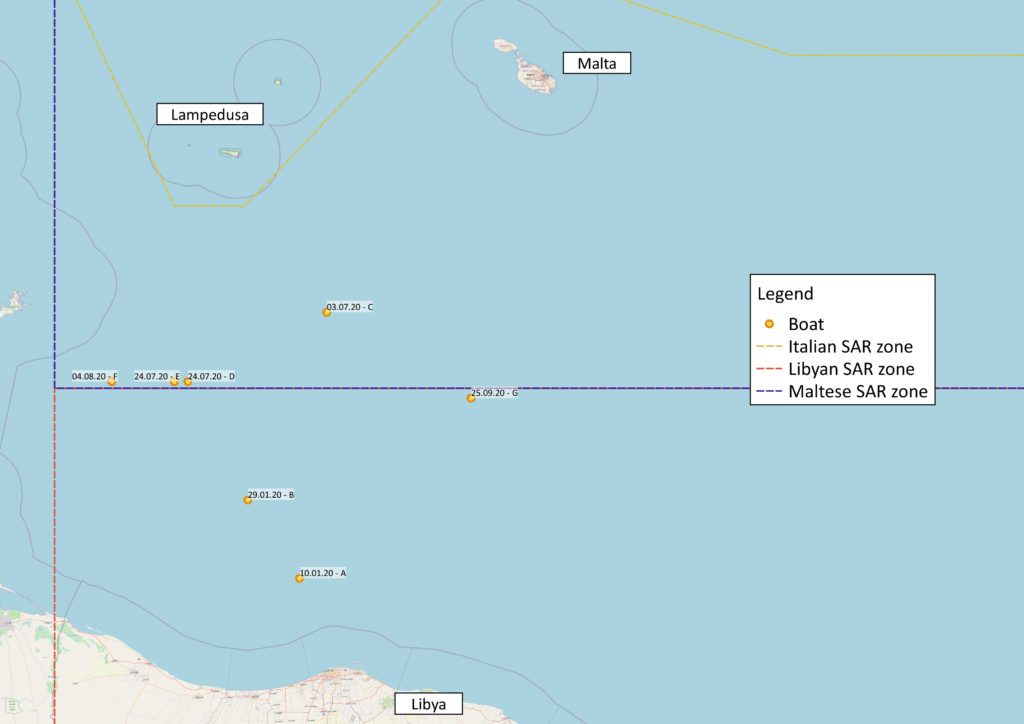

Maltese Search-and-Rescue (SAR) zone

1 distress case was rescued by the merchant vessel Talia, transshipped to a Maltese patrol boat and disembarked in Malta

1 distress case was rescued by the merchant vessel Cosmo and disembarked in Italy

1 distress case was intercepted by the so-called Libyan Coast Guard and pulled-back to Libya

1 distress case was rescued by the merchant vessel Maersk Etienne, and later transshipped to the NGO vessel Mare Jonio before being disembarked in Italy

Estimated** number of persons in distress: around 259

Libyan Search-and-Rescue (SAR) zone

2 distress cases were intercepted by the so-called Libyan Coast Guard and pulled back to Libya

1 distress case was rescued by the NGO vessel Open Arms and disembarked in Italy

Estimated number of persons in distress: around 250

Details and Outcomes of the Distress Cases

10.01., distress case A, around 70 persons: non-assistance of 2 merchant vessels and pullback to Libya. Moonbird’s crew spotted the people in the Libyan SAR zone, with some life vests and a running engine. The vessels Asso Ventiquattro and Asso Ventotto, both flying the Italian flag, were around 5,9 and 5,6 nautical miles (nm)*** respectively from the last known position of the distress case. Asso Ventiquattro’s crew was responsive to Moonbird’s crew but stated that they had no permission to leave oil platform ENSCO 5004 at which they were working. Asso Ventiquattro’s crew told Moonbird’s crew that they would ask the oil rig for permission to leave and that a Libyan officer was on the platform. Asso Ventotto’s crew stated that they were also waiting for orders from the Libyan authorities. Airborne informed the Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) about Asso Ventiquattro being in the vicinity of the distress case, but the authority did not reply. Airborne also tried to call Asso Ventiquattro and Asso Ventotto’s shipowner, Augusta Offshore S.p.A. The operator talked briefly with another person and hung up before forwarding to the responsible person. The number of the company operating ENSCO 5004 did not work. Since contacts with the shipping companies were unsuccessful, Airborne contacted the Italian shipowners’ association Confitarma, which took the information and stated that they would see what they could do – though the association did not provide any further information. Later that day, the people in distress were intercepted by the so-called Libyan Coast Guard and disembarked in Libya.

29.01., distress case B, 45 persons: 2 merchant vessels stood-by and provided water, rescue operation carried out by the civil fleet. The people in distress called the initiative Watch The Med – Alarm Phone which alerted the responsible authorities. Moonbird’s crew spotted the 45 people in distress in the Libyan SAR zone. The merchant vessel Asso Venticinque, flying the Italian flag, was in the vicinity. Moonbird’s crew was able to reach out to the crew of Asso Venticinque which informed them that the vessel was standing-by, “with the instructions to wait for the merchant vessel OOC Panther”, flying the Liberian flag, to arrive. It is still unclear who gave the order. The OOC Panther was around 8 nm from the people in distress, heading to the position. Its crew told Moonbird’s crew that they would assess the situation. A patrol boat of the so-called Libyan Coast Guard was also spotted in the vicinity. Both shipowners, Augusta Offshore S.p.A and Opielok, as well as their shipowners’ associations, Confitarma and Verband Deutscher Reeder (VDR), were contacted with the information that their vessels were close to a distress case, but did not reply to Sea-Watch. Since the Asso Venticinque was flying the Italian flag, the Italian MRCC was informed of its presence in the vicinity, though the MRCC did not share any information with us. Moonbird’s crew later spotted the so-called Libyan Coast Guard heading in the opposite direction, away from the people in distress. In the meantime the OOC Panther arrived on-scene and provided the people with water. After none of the actors present took the people on board for several hours, they were eventually rescued by the NGO vessel Open Arms and disembarked in Messina, Italy on 15.01.

03.07., distress case C, 52 persons: European authorities denied a port of safety to a merchant vessel that complied with its duty to rescue. The initiative Watch The Med – Alarm Phone alerted authorities about a distress case, which was found in the morning by Seabird’s crew in the Maltese SAR zone. The livestock carrier Talia, flying the Lebanese flag, was the nearest and only ship in the vicinity and changed its course to monitor the distress case. Meanwhile, when Airborne called the Maltese Rescue Coordination Centre (RCC), they refused to take any information and hung up with the words “we don’t speak with NGOs”. In the evening the weather became worse and the Talia, as ordered before by the Maltese authorities (which had an aircraft on scene), rescued the people. The Maltese authorities had promised a transshipment of the rescued people onto an Armed Forces of Malta vessel, but then instead advised the Talia to sail to Lampedusa, using the bad weather as an argument. The Italian authorities denied the Talia‘s entry to Italian territorial waters and instructed the vessel to sail to Malta. Later, the Maltese RCC initially refused the Talia entry to Maltese territorial waters, though eventually agreed to let her anchor in territorial waters on 04.07., so that she could seek shelter from high waves. Neither the Italian authorities nor the Maltese RCC accepted to declare themselves as “competent authorities” for this rescue operation, although the rescue took place in the Maltese SAR zone and therefore the RCC Malta was obliged to coordinate and organize the disembarkation. Several rescued persons showed symptoms of sickness, and 1 person had to be evacuated to Malta for medical reasons. After spending 5 days in inhumane and degrading conditions on a merchant vessel that normally transports livestock, the rescued people were finally transferred to a Maltese patrol boat and disembarked in Malta on the evening of 07.07., with the support of civil society, many other actors and a lot of media coverage.

24.07., distress cases D, E, respectively 108 and 72 persons: rescue operation by a merchant vessel and interception in the Maltese SAR zone coordinated by the Maltese authorities. In both cases, the people in distress had called Watch The Med – Alarm Phone, which had alerted the authorities. When Moonbird’s crew spotted the people in both boats, they were only 2 nm away from one another. The oil/chemical tanker Cosmo, flying the Italian flag, was instructed by the Maltese authorities, also present with an aircraft, to monitor both cases. After distress case D had been in a situation of severe danger for several hours, with the boat’s tube being deflated and the people having to remove water from the boat with their hands, the people on board were finally rescued by the Cosmo. However, the people of distress case E were intercepted in the Maltese SAR zone by the so-called Libyan Coast Guard and disembarked in Libya. During the interception, the so-called Libyan Coast Guard also demanded of the Cosmo that it hand over the people from distress case D, who were already on board the Cosmo. This request was refused by the captain of the Cosmo, who disembarked the rescued persons aboard his vessel in Italy.

04.08., distress case F, 27 persons: Maersk Etienne: longest standoff in SAR history, European authorities denied a port of safety for more than 5 weeks to a merchant vessel that complied with its duty to rescue. The initiative Watch The Med – Alarm Phone was called by the people in distress and alerted the authorities. Moonbird’s crew spotted the people in the Maltese SAR zone with the offshore supply vessel Maridive 601, flying the Belizean flag, in the vicinity. The Maridive 601 was however unresponsive on the radio. The chemical/oil tanker Maersk Etienne, flying the Danish flag, was 11 nm away from the boat. She changed course and headed to the position. The Maersk Etienne crew secured the boat and provided assistance but did not rescue at first, because RCC Malta had instructed them only to stay on scene and await a rescue asset. The persons in distress were then successfully rescued by the Maersk Etienne in the evening, as the weather was deteriorating. The vessel set its course to Malta, as Maltese authorities were aware of this case and had given instructions to the vessel. However, although the Maltese authorities had begun to coordinate the distress case, they were not willing to let the rescued people disembark in Malta. The Maersk Etienne waited for more than 5 weeks outside Maltese territorial waters, the request for a port of disembarkation having been denied by Maltese and Tunisian authorities. 3 people even jumped overboard out of desperation and had to be rescued by the crew. The people were finally transshipped to the NGO vessel Mare Jonio on 11.09 and disembarked in Pozzallo, Italy, on 12.09.

25.09., distress case G, 135 persons: 3 dead persons, the so-called Libyan Coast Guard refused to retrieve 1 corpse, a merchant vessel chose rather to let people in distress get intercepted than hinder a pullback to Libya. Seabird’s crew overheard on the radio the merchant vessel Cape Guinea, flying the flag of the Marshall Islands, sheltering a distress case and communicating to the so-called Libyan Coast Guard that 1 person was in the water. The so-called Libyan Coast Guard then ordered the Cape Guinea to leave the scene, as their patrol boat was approaching. Once Seabird was on-scene, the crew spotted the persons in distress in the Libyan SAR zone, with 2 persons in the water and 1 dead body. The Cape Guinea was sailing away. Seabird’s crew later observed the interception of the people by the so-called Libyan Coast Guard. Both people in the water were taken on board, the so-called Libyan Coast Guard refused however to recover the dead body. After completing the interception, they confirmed on the radio to Seabird’s crew that there were 2 other dead persons, probably found inside the rubber boat. The people in distress were pulled-back to Libya. The survivors later reported to the IOM that 15 persons had died.

These cases highlight:

- The continuous involvement of merchant vessels in SAR events due to the lack of European rescue assets in the Central Mediterranean

- The lack of support from the authorities for merchant vessels engaged in rescue operations and the resulting unjustified failures of some merchant vessels to assist persons in distress

- The use of power and intimidation by authorities over merchant vessels, leading to non-assistance and pullbacks to Libya

- The support of civil society for merchant vessels engaged in sea rescue operations

- The current systematic passing of responsibilities between Malta and Italy for the disembarkation of rescued persons onboard merchant vessels

- The need for a European state-led sea rescue programme in the Central Mediterranean in order to uphold the law, relieve the shipping industry and save human lives

* Since 2017, together with the Swiss NGO Humanitarian Pilots Initiative, Sea-Watch monitors the Central Mediterranean with its aircraft Moonbird and more recently Seabird.

**These numbers are based upon the estimations of Moonbird and Seabird’s crew, as well as numbers which the initiative Watch The Med – Alarm Phone, the UNHCR and IOM have provided to us.

***“Nautical miles” (nm) is the unit of measurement used at sea. 1 nautical mile is equal to 1,852 kilometers.